I SHOT ARNOLD

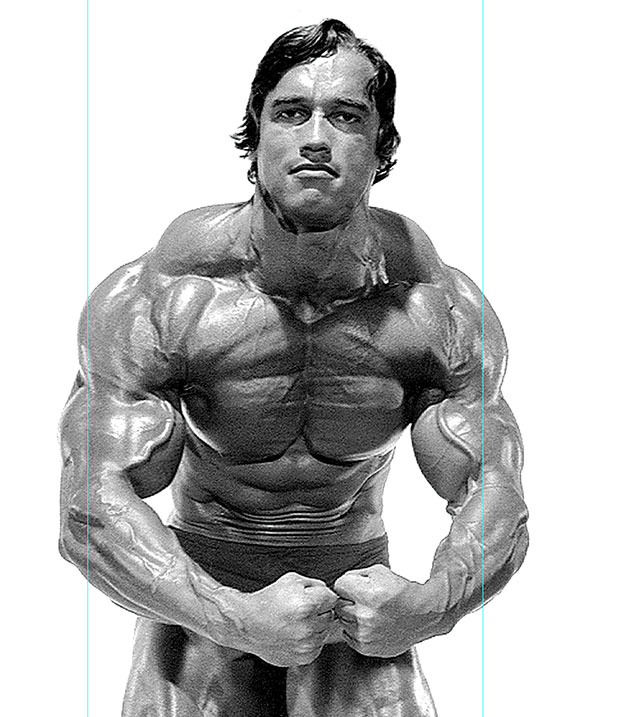

Setting sights on a legend: The men who photographed Schwarzenegger.

From the time Arnold Schwarzenegger came on the bodybuilding scene, he was not only a major champion but a master publicist as well. Arnold has always had the knack of attracting attention and getting a lot of media coverage—sort of like one of the US presidential candidates we see on TV every day. No matter where he went or what he did, he was always the centre of attention.

But this didn’t come about entirely because of his great physique and colourful personality. Arnold grew up looking at photos of legendary bodybuilders in the magazines. He saw Steve Reeves in Hercules and his great hero Reg Park starring in various Italian muscle movies. He realized that only a relatively few fans would get to see him in person, but if he made an effort to get as many great photos of himself out there as possible, he could reach millions.

So, unlike many of his contemporaries, who had to be talked into photo shoots and weren’t always 100 percent cooperative, Arnold was his own publicist and made sure he did as many photo shoots with the right photographers as possible. In this article, we talk to some of the men who shot Arnold and find out what their experiences were like.

GENE MOZEE

Gene Mozee was originally a bodybuilder and the first lifter to bench 400 pounds with a two-second pause—at a body weight of only 200 pounds. So it’s understandable that his introduction to Arnold Schwarzenegger was by way of a bench press. Gene was working out at Vince’s Gym in Los Angeles in 1969 when Arnold began training there. The two started benching together.

When Arnold first began training at Vince’s, Joe Weider asked Gene to keep an eye on him. Weider was concerned about some of the “goofballs” that might have a bad influence on his newly arrived protégé and the temptations of LA. Joe had great hopes for the future of this big, young Mr. Universe and intended to fill the pages of Muscle Builder (the forerunner of Muscle & Fitness) with his images. Gene had been the editor of the magazine from 1964 to 1968, so it was natural for Weider to turn to him for articles on and photos of Arnold.

Gene had formerly been the editor in chief and writer at Physical Power magazine, and he had gotten into photography as a kind of practical necessity. “We had a lot of articles for which we needed photographs. I picked up a camera and started shooting just so we could have illustrations to go with the text. I only knew the basics at first, but I found I had a real love of photography, so I set out to learn as much as I could.” One of his mentors at the time was master photographer Russ Warner, who was very willing to share knowledge of photo technique.

“Actually,” Gene believes, “almost all the best bodybuilding photographers have been bodybuilders themselves. Even Russ Warner, who didn’t compete, did some serious gym training. It takes specialized knowledge to know what the poses are supposed to look like and whether a bodybuilder is hitting poses in a way that makes him look the best and create effective photos.”

“My first photo session with Arnold was at Venice Beach,” Gene recalls. “I was very impressed with his professionalism. He showed up on time, ready to work. He knew exactly what poses were best for him and how best to hit them. There was no mirror for him to look into, of course, so he would take suggestions as to how to make small adjustments to improve the photograph. He was not at all difficult to work with. Arnold understood the value of good publicity photos, and he was willing to do his part to get the best pictures possible.”

Arnold, Gene discovered, was not into experimentation when it came to posing. He worked very hard on finding and mastering poses that showed his physique at its best. “He had a limited number of poses, but they were perfect. If you look at photos by different photographers or pictures of Arnold onstage, you always see the same poses. But in a posing routine, he had a way of presenting himself in a very dramatic and commanding fashion. And given his track record of championship wins, you have to conclude he knew what he was doing.”

Gene Mozee says he only photographed Arnold a few times, mostly outdoors, but he interviewed him dozens of times for the Weider magazines. He does think getting to train with Arnold was an advantage. “When I was able to work out with bodybuilders like Arnold, Larry Scott, or Don Howorth, I think I developed a lot greater appreciation as to what their physiques were really like. This also led to a better rapport. So when we would do a photo session I had a kind of head start in figuring out how best to shoot them.”

ART ZELLER

Many of the best photos of Arnold, especially from early in his career, were shot by the late Artie Zeller.

When Zeller first started shooting photos in the 1950s, a lot of bodybuilding pictures were done for a largely homoerotic audience. But he was determined to create photos of bodybuilders that captured what they had been able to achieve in developing the aesthetic qualities of their muscles and making bodybuilding more accessible to the mainstream.

Zeller began shooting photos for Joe Weider when the magazines were still located back east, and when the company migrated to LA, he decided to follow.

When Arnold first came to LA, he became friends with and started shooting photos with Zeller. Arnold had a lot of respect for Artie’s photography, which he had seen and admired since he first got into the sport as a teen. Artie had himself been a old-school bodybuilder—a contemporary of legends such as Steve Reeves, Bill Pearl, Reg Park, and others that Arnold viewed as heroes and often mentors.

“In the evening,” Arnold wrote in his autobiography, Total Recall, “I often hung around with Artie Zeller, the photographer who’d picked me up at the airport. Artie fascinated me. He was very, very smart, yet he had absolutely no ambition. He didn’t like stress, and he didn’t like risk. He worked behind the window in the post office. He came from Brooklyn, where his father was an important cantor in the Jewish community; a very erudite guy. Artie went his own way, getting into bodybuilding in Coney Island. Working as a freelancer for Weider, he’d become the best photographer of the sport. He was fascinating because he was self-taught.”

Joe Weider, according to the German Wikipedia, described Zeller’s talent like this: “Technically speaking, Artie was more of a gifted amateur than a polished pro. But his rapport with the guys and his deep understanding made his pictures something special.”

Zeller was never a polished studio photographer, and his best work was in black and white. He excelled at outdoor photos such as the ones he did with Arnold, Dave Draper, and others posing on the rocks in the hills above Malibu. These were usually shot with a 35mm camera, without the help of portable strobes or reflectors. What helped set his work apart was not technique but the fact that he was getting these legendary bodybuilders to pose in such dramatic settings, that they enjoyed shooting with him and were very cooperative, and that he had a good eye and a lot of experience and knew what would show the best qualities of his subjects.

It certainly helped when shooting Arnold that he and the Austrian Oak got along so well and were friends.

Another quality that endeared Zeller to Arnold was his humour. Artie would start telling jokes, one after another, that often tended to be crude and sexual, and Arnold couldn’t get enough of this. It turned out they had pretty much the same taste when it came to comedy. While others in a group might be wondering how they could get Artie to shut up, Arnold would keep egging him on to keep it up. Artie was a kind of court jester in Arnold’s circle of friends and admirers.

Artie Zeller died of pancreatic cancer a few years ago. Arnold remained a friend and admirer to the end. To provide financial support for Artie and his wife, Arnold arranged to purchase the entire catalogue of Zeller photos of him for quite a substantial sum.

JOHN BALIK

In 1969, John Balik—eventually to become publisher of Iron Man—was a young bodybuilder working part-time in the LA gym owned by Vince Gironda. And he was a photographer.

“Arnold had just moved to LA after losing to Frank Zane at the 1969 Mr. Universe. He began training at Vince’s, and I would see him shooting with Art Zeller. Arnold was always enthusiastic about doing shoots with anyone whose photos he liked, so I began working with him as well.”

Nowadays, getting top pro bodybuilders to schedule and show up for photo shoots can be like herding cats or pushing rope. Very few want to do photo sessions before a contest, and many don’t stay in top shape for more than a day or two afterwards. There are often managers and publicists to deal with, and some need to be paid substantial amounts before they agree to pose for pictures.

“Arnold realized that his achievement was how his body looked and how he presented it, but that this was something that was not permanent and would change very quickly. Good photographs were the way to capture and preserve his accomplishments for all time,” says Balik.

He also knew that a relatively few see you in person, but potentially millions will end up seeing your photographs.

John Balik remembers that, unlike most bodybuilders today who only like to do photos after a contest, Arnold would schedule a lot of photo shoots in the two weeks before a competition. And you didn’t have to do any great looking for him. He could seek you out. You’d get a phone call from Arnold suggesting a time and place to do a photo session. So you’d pack up your cameras and just show up.

Arnold had no inhibitions about showing his body during this pre-contest period (unlike contemporary competitors who often remain swathed in layers of sweatshirts as contest time approaches). Rather than a distraction, Arnold saw the flexing and posing demanded by photo sessions as a way of helping him to get in better condition and prepare for the demands of posing onstage during a contest.

“One thing that was always true with an Arnold photo shoot,” recalls John Balik, “is that they were always fun. Arnold used to say that he always had a good time no matter what he was doing, and that was true when he did photos. He was never difficult to deal with, was always joking and making everybody else smile.”

One thing about Arnold photos is that you will always see him doing Arnold poses. Arnold developed a set of specific poses and concentrated on perfecting them. He was very aware of his own weak points (which every bodybuilder has) and posed in such a way to draw attention away from them and to his most outstanding body parts.

“Arnold always did his own poses,” John Balik agrees, “but he was always open to suggestion as to how to maximize their effect in photo sessions. If I would make a suggestion as to how to make small changes to make for a better photo, Arnold would listen and consider my input. He was never argumentative. Arnold was always a learning machine and never cut himself off from sources of help or information.”

One thing John Balik recalls about Arnold was his excellent muscle control. “Watching Arnold, when he hit poses he had every muscle and muscle control totally under control. Hitting a back shot, like his famous twisting back pose, every muscle involved was flexed as it should be. I see a lot of top pro nowadays, even on the Olympia stage, about whom that is not true. They are huge, impressive, and in great shape—but a lot of muscles that should be flexed just aren’t.”

Just look at Arnold doing a stomach vacuum. He is as effective in that pose as Frank Zane, who was so much smaller. Stomach vacuums are not a post most of the bigger pros of today seem to be capable of.

While John Balik admires and respects today’s bodybuilders, most of whom he has featured in Iron Man, he has a fondness for the “golden age” of the ‘60s and ‘70s, which were more innocent times by comparison. Top competitors trained together, hung out and socialized together, went out for chicken on all-you-can-eat night at Dinah’s in LA, and saw shooting with top magazine photographers as a great opportunity rather than a chore.

And they were much more accessible to photographers.

“Nowadays,” John Balik points out, “bodybuilders are more dispersed in a lot of different gyms, the magazines no longer have the importance they did, and there are so many photos by so many photographers of different ability being uploaded to the Internet that the better pictures are easily overwhelmed by those that are not so good. So the excitement of a really good photo session is frequently not as much as it was thirty or forty years ago.”

But times change and the potential of digital cameras, Photoshop, and the ability to shoot HD images and settings that allow for quality photos in almost no light create the potential for a new golden age to come.

It’s just unlikely that future photographers will have the benefit of having such an interesting, colourful, and cooperative subject to work with as the amazing Mr. Schwarzenegger.

AL SATTERWHITE

While Arnold has been photographed by most of the top shooters in the bodybuilding world, over the years he has also worked with some of the best known mainstream photographers. These have included legendary Hollywood studio photographer George Hurrell and Vanity Fair superstar Annie Leibovitz. But one of the first to do photo sessions with him back in the 1970s was noted editorial photographer Al Satterwhite.

“Actually,” Satterwhite explains, “although I had heard of Arnold, I really didn’t know much about him. But in 1976 I was contacted by Bunte magazine in Germany and given the assignment of shooting a picture story on him. I ended up doing several photo sessions with Arnold over a period over about a week.”

Al Satterwhite started working as a photographer at a major daily newspaper in Florida while in high school, covering major news stories in the southeast. After a year as the governor of Florida’s personal photographer, he started a career as a freelance magazine photographer. Over the next 10 years, he worked on assignments for almost every major magazine (Car & Driver, Fortune, Life, Newsweek, People, Playboy, Sports Illustrated, and Time, to name a few).

Pumping Iron had been published in 1974, but Satterwhite had never seen it—nor the photos in the book by George Butler or the movie Stay Hungry. So when he sat down to lunch with Arnold for the first time, his first impression was simply of a very big young man with a very thick Austrian accent. But within a few minutes he realized he wasn’t dealing with some big, dumb athlete. “It was very apparent,” Satterwhite recalls, “that Arnold was very smart, extremely perceptive, and had a great sense of humour. So I realized this assignment was probably going to be more interesting than I had first thought.”

Over the next week they did photos at Gold’s Gym, a couple of restaurants, a trap shooting range, and Venice Beach, both at Muscle Beach and down on the sand. Satterwhite was using a very wide-angle 15mm lens part of the time, and Arnold asked to look through the viewfinder to see what it looked like. Shooting down near the water, another photographer started shooting pictures. Arnold stopped and spent a few minutes hitting poses for this paparazzo. But when he went back to shooting with Satterwhite, the other photographer kept shooting—until Arnold turned to him and said, “Are you going to go away, or do I have to stick that camera up your ass?”

It should come as no surprise that the other photographer left in a hurry.

Throughout the week, the photographer found Arnold to be very cooperative and full of energy throughout each photo session—an ideal subject. The Oak also kept things light with his sense of humour, making a lot of jokes as they worked together on the photographs.

Satterwhite sent in his assignment, and it was very well received in Germany. “Actually,” he says, “I never worked with Arnold or even met him again after those photo sessions. Of course, I had no idea he was going to become a major movie star or governor of California. But I wasn’t shocked, either. Somebody that bright and funny was obviously in a great position to take advantage of opportunities that happen to come his way.

Nowadays, Al Satterwhite has moved from editorial to fine art photography. His photographic prints are in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Santa Barbara Museum of Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; George Eastman Museum; Polaroid Collection; National Museum of African American History and Culture and numerous private collections. And, of course, his photographs of Arnold are available as part of his fine art catalogue.

JIMMY CARUSO

As a young man, Jimmy Caruso and Joe Weider both lived in Montreal and knew each other. Caruso ran a gym and was training a lot of young bodybuilders. At one point, he became very dissatisfied with the kinds of photos the bodybuilders were getting, so he decided to try to do better himself. “This was the mid-1950s,” he recalls, “and I didn’t know anything about photography. So when I got hold of a camera and started trying to do physique photos, the results were really terrible. I went to my local photo store and asked them about this. They tried to explain about things like film types, exposure, development, and printing, but it all seemed way too complicated. So at that point I didn’t pursue photography further.”

But still frustrated with the poor photos he saw of excellent physiques, Caruso decided to plunge ahead and learn what he needed to about the techniques and technicalities involved in making quality photographs. “I purchased the necessary cameras and lenses, lighting, and darkroom equipment, and started developing and printing my own photos. When you have to develop and print your shots, you learn to correct your mistakes very quickly. So my work quickly got a lot better, and I quickly developed a love of photography I would not have anticipated.

At that point, Joe Weider was developing what would become a publishing empire, and when he saw Caruso’s photos, he began using his pictures for his magazines. He sent to bodybuilders to Montreal from places such as New York and Los Angeles and flew Caruso and his cameras to various locations where there were bodybuilders and bodybuilding events.

“In 1968,” Caruso recalls, “Weider brought Arnold Schwarzenegger from Germany to Florida to compete in the IFBB Mr. Universe contest. Weider also arranged for me to be in Florida to do photos, and I would go out on the beach and do photo sessions with Arnold. Arnold was extremely impressive—big and with great symmetry. He was also extremely cooperative and easy to work with, always very pleasant and joking around—in spite of the fact that his English was not very good at the time.”

We all know Arnold as a powerful and dynamic poser, but Caruso explains that mastering posing was something the Austrian Oak had to work on over time. “One of the things I brought to shooting pictures of bodybuilders was the ability to help them fine-tune their posing. Arnold was a good poser, but there was certainly room for improvement. After all, he couldn’t see himself when he posed, and coming from Germany, he wasn’t able to get the kind of advice and info that would allow him to perfect his poses and allow him to show off his body to its absolute best advantage.”

During their photo sessions, Caruso would give Arnold suggestions to make his poses more effective. He says that rather than being reluctant to take coaching, Arnold was enthusiastic about making adjustments to help become a better poses. “Once Arnold started seeing the actual photos,” Caruso explains, “he was even more eager to continuing making improvements. He could see the results and the degree to which different ways of posing helped him to look better. Arnold has always been described as a ‘learning machine,’ so once he saw the benefits of our photo session and my feedback regarding his posing he was more motivated than ever to keep shooting.”

Joe Weider continued to set up Caruso photo sessions with Arnold over the years, getting them together in Montreal, New York, and Los Angeles. During that period of the 1960s and 1970s, no other photographer in the industry could produce the quality of studio photography that Caruso achieved, so his work was published on a regular basis in Muscle & Fitness and Flex. He created a body of work that magnificently captures the bodybuilders of that era, particularly Arnold.

At age 90, Caruso continues to work with young bodybuilders, including helping them to perfect their posing routines. He admires the development of today’s top pros but regrets the fact that most of them make no real effort to create the aesthetic poses that he has always considered so essential to the sport.

“Posing today is so much about mass and muscularity,” he says. “For the most part, aesthetics is being ignored. We no longer have the concept of the ‘body beautiful’ that existed when I began doing physique photography. I know times change, but I’d like to see more of the top pro bodybuilders think in terms of aesthetics rather than just overwhelming mass. And I wish I were still in a position to help them with this.”

GEORGE BUTLER

You cannot write about the men who shot Arnold without mentioning George Butler. His photos of Arnold are some of the greatest of all time. It’s no wonder that MUSCLE INSIDER has used his images for our cover three times already (pictured at right).

While covering the 1972 Mr. East Coast for Sports Illustrated, Butler and writer George Gaines noticed that the crowd was going nuts for the bodybuilders onstage. But when the photo editor for SI looked at the photos Butler handed in, he said, “This is the last time SI covers bodybuilding.”

But the two were hooked. They managed to secure an advance from publisher Doubleday for a book on bodybuilding. However, when they turned in the manuscript for Pumping Iron, the agent at Doubleday said, “No one will ever buy this book. You are a disgrace and have wasted all the money we gave you.”

Despite the harsh remarks, Butler and Gaines believed bodybuilding would still become a big mainstream hit. Butler then went to Simon & Schuster. Bigger than Doubleday, they could afford to take a gamble on the book. Through superior sales and marketing, Pumping Iron was on the best-seller list before it hit the stores. By the time it did, it was already in its fifth printing. That’s when Butler knew bodybuilding was getting big.

To publicize the book, Butler hired a few bodybuilders, including a relatively unknown guy named Arnold Schwarzenegger, to give an exhibition at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. That’s where Butler first met Arnold. Butler said, “He was very impressive, and I wanted to shoot him. I called one of my contacts at the Village Voice and talked them into the assignment. Those pictures we shot at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for the Village Voice were the first time Arnold’s pictures had ever been seen outside of bodybuilding.”

Soon after, the idea for the Pumping Iron documentary was formed and then eventually realized. When the film debuted and the world got to meet Arnold Schwarzenegger, the rest, as they say, is history. Pumping Iron would forever link George Butler and Arnold’s names in bodybuilding lore.

The two would meet again in Sydney, Australia, in 1980 when Arnold returned to competition for one last Mr. O title and George was there to capture his win with his trusty camera.

For more about Arnold and why he's still important and relevant in this day and age, click here!